Mediafication: How Media Rewires The World

The main aim of this article is to show how the media facilitates economic growth of companies and individuals.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. A Brief History of Media

2.1. The age of typography

2.2. The age of electricity

2.3. The age of the internet

3. Major Trends in Media

3.1. Higher audience participation

3.2. The convergence of production and distribution functions

3.3. Everyone is a media producer

3.4. The rise of the subscription business model and niche media

3.5. The importance of content cross-pollination

4. Publishers and Platforms

4.1. Editorial vs. Business — Diminishing power of the latter

4.2. Medium: a publisher or a platform?

4.3. Vox Media: a platform play

4.4. Substack: a platform for independent writers

5. Selling content vs. selling using content

6. Conclusion: New Markets and Opportunities

6.1. Summary: The Future of Media and Publishing

1. Introduction

Each technological revolution makes information more accessible — cheaper to produce and distribute. The invention of the printing press, harnessing of electricity, and development of the internet each revolutionized information infrastructures. In fact, content has become a product — although intangible — of increasing value that is infinitely reproducible at almost zero cost.

Over the last few decades, software has become an integral part of every business. Every business is a software business. And knowledge workers interact with a variety of software products on a daily basis.

However, what might be less obvious, but more impactful, is how technology has changed and redefined the way we produce, distribute, and consume media. Like software, media is no longer limited by the boundaries of its own industry — it’s a new and important layer that underpins the economy for businesses and individuals. Today, every company is a media company.

Arguably, the impact of “mediafication” on the economy will be as great or even greater than the impact we experienced from the software "eating the world." The reason is simple — it’s much easier for individuals to produce content than to create software.

The main aim of this article is to show how the media facilitates economic growth of companies and individuals. It will cover important trends and discuss how companies have to adjust and start running their companies as media organizations. More individuals will build their businesses in media or using media as a primary growth channel.

New kinds of publishers and platforms are emerging and we'll cover a few of them. And finally, we’ll talk about how mediafication will spark the growth of many new products and platforms to build a new infrastructure for producing, publishing, distributing, engaging, and analyzing content.

Let's start by defining a few terms frequently cited in this article.

Information is an umbrella term that defines all data exchange, meaningful or not.

Content is an informational product that's meaningful and contextual. It consists of information units linked with meaning and context.

Media is a system of communication that incorporates a set of content production and distribution processes.

Mediafication (invented term) is a process of introducing a media layer, with its processes related to content production and distribution, into every aspect of the economic relationship.

Medium is a channel through which content is published and distributed. Medium and channel will be used interchangeably in this article.

Publishing traditionally has been defined as a print medium or textual. In this article, the term publishing and media will be used interchangeably because both are closely related to content production and distribution.

2. A Brief History of Media

Typography, electricity, and the internet are the three great media revolutions.

2.1. The age of typography

The birth of modern media can be directly linked to the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg. This new technology allowed ideas and information to spread at an unthinkably fast pace, at least by 15th-century standards. By 1500, only two decades after Gutenberg's invention, all printing presses in Western Europe had already produced more than 20 million volumes (1). It's a significant number when you consider that books were previously produced by hand.

The printing revolution is also responsible for inventing new media - print - and the modern newspaper. The cost of printing fell drastically in the first century after the invention of the printing press. And by the early 17th century, newspapers were born. For the first time in history, the press provided political, military, and economic news and commentary for a broader general public.

The press in the form of newsletters, newspapers, gazettes, pamphlets, and bulletins changed how quickly and widely ideas spread. The new media allowed philosophers, writers, and scientists to share ideas in shorter forms. Before writing a book, authors could first express their concepts in a shorter and cheaper format of an article or a pamphlet. Newspapers included multiple topics and with a much lower price than a typical book, gave larger audiences access to new content. It can be argued that the age of enlightenment would have never occurred or at least had taken much longer if it wasn't for the printing press. Because what was the age of enlightenment other than a rapid circulation of new ideas and philosophies?

The press fundamentally shifted the balance of power between elites and the working class. A great number of people gained access to information and a way of spreading their own ideas. The growth in literacy rates in the world is directly linked to the invention of the printing press (2),(3).

2.2. The age of electricity

Before the mid 19th century, information could travel only as fast as human beings could carry it. Or to be more accurate, as fast as horses can carry a messenger. The invention of electricity enabled information to move across greater distances in shorter times. The electrical telegraph, invented by Samuel Morse, connected distant places and, for the first time in history, allowed almost real-time communication. Neil Postman calls Morse the first “spaceman” for the fact that his invention collapsed state lines and created a possibility for the unified American conversation.

But the age of electricity was only getting started with the telegraph. The telephone, photography, motion pictures, and radio were invented during this time or soon after. They opened a Pandora's box of new media that would transform every corner of our life. In its golden age, between 1930 and 1945, radio became an indispensable part of political, economic, and social life in the developed world. The percentage of households that owned a radio grew from 40% in 1930 to 83% a decade later (4). Franklin D. Roosevelt became the first radio president in the US. He used radio to speak directly to the American people, initially as a Governor of New York, then as a presidential candidate, and ultimately as the president of the United States.

By the mid 20th century, television became a new medium that added a visual dimension to broadcasting. For the first time, a large audience could not only listen but also observe announcers and anchormen. Television has changed how we discover and buy products. But it also changed our homes. Our living rooms expanded in size to accommodate a family entertainment space centered around a TV set (5). TV has changed every aspect of our society, from political to economic and social. The Kennedy-Nixon debates in 1960 were the first televised presidential debates and attracted an enormous audience of about 74 million viewers (6). For the first time in American history, presidential candidates could debate each other and the whole nation could see it in their living rooms, forever changing the way presidential candidates would campaign.

Nixon looked tired and sick. Kennedy looked rested and prepared. John F. Kennedy became the first TV president. Many experts claimed that people who watched the debate on television overwhelmingly believed Kennedy had won, while those who listened to the debate on the radio (a much smaller audience) thought Nixon had performed better (7).

The Kennedy-Nixon debates provide a clear example of how our perceptions change depending on the medium. The image of the speaker on television brings a powerful new dimension of how the content is evaluated by the audience. As Marshall McLuhan later explained, the medium is the message, which means that the nature of a medium is more important than the meaning or content of the message (8).

2.3. The age of the internet

In the age of the internet, the rate of new media and technology adoption is staggering. The internet is a child of the electronic age, but because it’s had such a transformative influence, it's really a whole new branch of media.

Interestingly, the adoption of every new medium accelerates over time. It took the telephone about 75 years from its creation to reach 50 million users. Radio did it in 38 years. TV gained 50 million users in 13 years, the internet in 4 years, and Facebook in 2 years (9). In early 2010, a widely popular mobile game, Angry Birds, posted a new high score by reaching 50 million users in 35 days but just six years later Pokemon Go would reach this mark in half the time. Only 19 days were necessary for Pokemon Go to attract the same audience (10).

- Telephone - 75 years

- Radio - 38 years

- Television - 13 years

- The Internet - 4 years

- Facebook - 2 years

- Angry Birds - 35 days

- Pokemon Go - 19 days

The audience for new media can increase exponentially because the infrastructure already exists, so no new hardware is necessary for consumers. And the increasing number of channels multiplies the efforts of driving the audience to a new medium.

As the printing press and electricity provided the foundation for the new media explosion, the internet became the backbone for new digital channels. The number of media channels grew exponentially with each new paradigm shift. While electricity created a few media (radio, TV, telegraph), the internet created thousands of new channels. And for every mature digital medium such as Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube, we have hundreds of new ones (Tiktok, Snapchat, etc). It's easy to see how each becomes a media channel of sorts, but more on this later.

As with the printing press, telegraph, radio, and TV, every newer medium becomes the dominant channel for public discourse in every area of our lives. Internet channels dominate current public discourse. The rise of Barack Obama from a freshman senator and unlikely presidential candidate to the presidency can be attributed not only to his charming personality and charisma but also to his, and his team’s, mastery of social media channels. Like Roosevelt and Kennedy before him, Obama embraced the new media landscape, which led many to claim that he was the first social media president (11),(12).

The new media do not replace the old ones. TV, radio, and telegraph did not replace books and newspapers. Similarly, the new digital channels enabled by the internet did not oust the most important medium of the previous age - television. Youtube hasn’t replaced TV or cable. Podcasting hasn’t replaced a traditional or satellite radio. On the contrary, both Youtube and podcasting provide good examples of how the content of previous media (TV and radio) can be used in creating new ones. A TV show that previously could be accessed only at a certain scheduled time and on a particular channel now can be made available any time to anyone on YouTube and without forced commercials breaks (thanks to ad-blocking).

3. Major Trends in Media

To understand how the media impacts our lives, let's outline the major trends.

- Higher audience participation: It's getting easier and easier for audiences to respond and provide feedback to content producers.

- The convergence of content production and distribution functions: Every company is a media company, with both content production and distribution.

- Everyone becomes a media producer: The growing number of media channels allows anyone to build their own audience that leads to political or industry influence and, potentially, to additional income.

- The rise of the subscription business model and niche media: Advertising was the primary source of revenue that led publications to grow audiences and required content that appeals to the masses. Subscriptions enable niche publications to monetize a smaller but highly engaged audience.

- The importance of content cross-pollination: In order to increase distribution, content producers must adjust their content to fit the format and characteristics of an increasing number of channels.

Let's dig into these trends with more details.

3.1. Higher audience participation

Traditional print media provides one-way communication between publishers and readers. Journalists write stories, publishers focus on distribution and revenue, and readers are, for the most part, information consumers. If you didn't like the article in the national or local newspaper, your only two options were to stop buying the publication or to write a letter to the editor. The latter required a deliberate effort, not to mention a high concern for the topic at hand. When print media dominated public conversations, its influence over public opinion and topics was centered around large publications. They had much of the control over what topics would be covered and whose opinions would be heard.

The electronic media — TV and radio — opened up two-way communication. TV shows invited regular people to participate. Radio stations allowed listeners to call in. And let’s not forget that the telephone allows anyone to easily reach TV channels, radio stations, and even newspaper editorial to voice their concerns and opinions. Electronic media-enabled audiences not only consume broadcast content but also participate in content creation and production process.

Mass media created mass products. Companies could reach millions of people and advertise their products. When there were just a few broadcast channels, the message had to be tailored to the mass market — the audience in the middle.

The rise of advertising and the PR industry is directly connected to the rise of media influence on the public. Public relations is useless if there is no public opinion. And public opinion can only be created by mass media that can reach a large enough audience to formulate that opinion.

But while TV and radio allowed audience participation in the content creation process, the internet removed almost all the lines between the content producers and consumers. The social media revolution unlocked the power for everyone from kids to grandparents to post photos, express an opinion, or record a video and share it with pretty much anyone across the world. Today, everyone is a publisher with an audience. For many, the audience pays only with their attention but for some, with a significant following, the audience provides a substantial income. If you pass the tipping point in your audience size you are almost guaranteed to find a way to monetize your reach.

3.2. The convergence of production and distribution functions

In the early 2000’s it became clear to forward-looking companies that every company is a media company. Making products was just one part of the successful equation. Content creation and distribution became an essential piece of the puzzle. Every organization that wants to succeed needs to produce content and fill the airwaves on the expanding number of new media channels. The battle for customer attention is brutal. Losing it almost certainly guarantees devastation to the organizations’ bottom line. And often, it means a slow decline and eventual death by irrelevance.

If we look closer to the evolution of media companies, we’ll notice the convergence of production and distribution function under each company. Netflix, Google, Apple, and Amazon first built large audiences through their core business and, now, all of them are investing enormous amounts of cash to produce their own shows, films, and other entertainment content (13). Conversely, Walt Disney Company launched Disney+ streaming services with a large portfolio of entertainment products already available for their customers. In other words, Disney realizes that content without an owned distribution channel is almost certainly under-monetized, leaving large piles of cash on the table.

3.3. Everyone is a media producer

Similarly, every individual is a media personality today. The cost of content production and distribution has fallen to almost nothing. We, the people, became media entities ourselves. We write, produce, record, publish, discover, share, curate, and distribute content. We build our own audiences, providing a basis for our influence and income.

Professional gamers make millions of dollars through streaming. Instagram influencers earn money from product placements. Bloggers sell a subscription to their content or provide it free, making money from courses, training, corporate consulting, and public speaking gigs.

Sam Harris and Tim Ferriss are great examples of modern media personalities. Both produce a wide variety of content and across multiple channels. Both have millions of dedicated followers. They publish books and articles. They host widely popular podcasts with millions of subscribers. Harris and Ferriss built media empires around their personal brands.

In the future, we should expect more politicians to come from non-political backgrounds. Their army of fans and massing online following will constitute the initial base of supporters. Don't rule out President Kayne West, Governor Lady Gaga, or Senator LeBron James. We already had a film-star President Ronald Reagan and Governor Terminator. Besides, can anyone forget the 2016 election? David Perell rightfully pointed out — “The influencers of today are the politicians of tomorrow. Candidates with reach have organic built-in distribution, access to owned data and organic customer insights, and lower get-out-the-vote costs. Media savviness will be an essential skill for political success.” (14)

Politics is the ultimate game of attention. However, there is little doubt that every industry is influenced by the new rules of media. Regardless of your career interests, building an audience tremendously enhances your chances of rising to the top of the industry. Are you an inspiring chef? Begin building your audience, maybe starting with your YouTube channel. Do you want to be a VC or angel investor? Start interviewing VCs on your podcasts. You will tap into their social circles and can eventually build an audience large enough for the right opportunity to come your way. Need an example? Just look at Harry Stebbings, who masterfully played VC egos while tapping into their existing audience to his advantage, to become an investor before the age of 20 (15). The examples are endless. Your career will accelerate proportionally to the size of the audience you accumulate.

Popularity contests aren't only relevant in high school settings anymore. The same dynamic is true in almost every career. No one understands this better than the Z generation. You can't blame young people for starting to grow their audiences sooner rather than later (16).

3.4. The rise of the subscription business model and niche media

Before the internet era, print newspapers had two primary sources of revenue — subscriptions and advertising. First, they sold subscriptions directly to consumers. One can argue that the recurring revenue business model wasn't invented by tech software companies at the turn of the twentieth century but just borrowed from other industries where long term financial security was a survival necessity. Large publications like The Washington Post or New York Times needed a consistent flow of revenue to pay their journalists. Annual newspaper subscriptions provided much-needed predictability.

Nevertheless, the majority of the revenue generated by print newspapers came from advertisers. The incentives for publications and advertisers were perfectly aligned. The former needed to grow their readership and the latter needed to reach as many potential customers as possible. Mass products require mass marketing, and mass marketing requires mass media.

The internet changed the playing field completely. Print publications, as well as TV stations, lost their near-monopoly on the information. In the pre-internet era, a few national and local newspapers dominated the public discourse. With the internet, thousands of new digital publications emerged. Why would anyone pay for a newspaper subscription when news and information are available online free of charge? The first decade or so of the internet era opened a floodgate of free digital content. Newspapers suffered. Subscriptions to the physical paper declined. Some of the pain was self-inflicted — publishers failed to recognize the decade-long shift of audiences from offline to online channels, forgetting or delaying building their own online presence.

The first law of advertising, if it ever was one, states that the advertising follows the audience. Losing readers to internet resources not only resulted in declining newspaper subscriptions but also forced advertising dollars to flow towards greener pastures. Advertisers turned toward the newer and more attractive, from a return-on-investment perspective, digital media.

Remember, mass products require mass media. Newspapers no longer had access to the mass of readers while the internet-enabled businesses built niche products and targeted more effectively. Digital ad platforms provided more transparent tracking and analytics. Along with more granular ad targeting, these platforms provided higher return-on-investment for corporate marketing budgets.

The internet reduced the barriers to entry into the publishing business. A couple of journalists could buy a domain, take a WordPress template, and start publishing their own stories. The technical side doesn't take longer than a couple of hours. In fact, many successful online publications of the internet generation started as simple blogs — The Huffington Post, Mashable, Techcrunch — just to name a few.

Soon it became clear that advertisers have an enormous amount of new ad supply to choose from. There are only so many advertising spots available in a given print newspaper. It was bad enough that publishers had to compete for eyeballs among the growing number of digital resources. Simultaneously, publishers had to compete with new advertisers like Google and Facebook that provide a better understanding of customer intent and improved targeting capabilities. Luring advertisers away from Google and Facebook, who control between 55% and 60% of total US digital ad spending, is an uphill battle (17). Throw Amazon into the mix and you get three corporate giants controlling almost 70% of the digital ad market in the United States (18). Moreover, we haven't even mentioned social media heavyweights such as Twitter and Snapchat, who bring a combined $3.5B in annual ad revenue, give or take (19).

It shouldn't be surprising that in order to survive, many publishers had to revert to the subscription-based business model as their primary source of revenue. Today, almost every major publication online relies on subscription revenue — The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, The Atlantic, and the list goes on.

In his excellent piece, Popping the Publishing Bubble, Ben Thompson explains the difference between publishers that pursue a niche model and scale model. Niche publishers focus on maximizing revenue per user through a subscription model. Scale publishers, according to Thompson, focus on maximizing readership and reach while generating advertising revenue. He draws a hard line between these two business models. He explains that niche and scale business models are not only different in monetization strategy but also require a different approach to content and editorial focus as well as the content presentation style (20). The publishers can't possibly do both, he argues.

Thompson wrote his analysis almost five years ago. Since then, most of the data is pointing to the fact that the subscription monetization model is gaining on the ad-based model. Research by Digiday, of more than a hundred media businesses in the US and UK, showed that more than half of them say subscriptions are the biggest contributor to revenue growth (21). The revenue from advertising is expected to drop by 8.6% in the next two years down to 53% of overall revenue. However, the revenue from subscriptions is expected to grow by 76.2% and reach 37% of total revenue (22). While the advertising budget still represents a larger portion of publishing revenues, it's clear that increasing competition and higher performing ad supply will force publishers to double down on the subscription model.

You don't have to be a niche publisher to capitalize on subscriptions. But it certainly helps if you focus on niche topics and smaller but more engaged audiences. Thompson's own publication, Stratechery, is a perfect example in this category. As publishers move to subscriptions the pressure to serve their smaller but highly engaged audience will naturally push publishers to more niche content segments.

Clearly, the subscription model is proving to be more effective and profitable for publishers. It's predictable and scalable. And more importantly, the subscription model enables publishers to build direct relationships with their readers. There is no need to appeal to mass audiences in order to cater to advertising dollars. The keys to success are more straightforward — create content that readers will pay for and design content experiences to help your audience to consume content anywhere, anytime. As a publisher, your only mission is to serve your readers, and your bottom line is directly correlated with how well you accomplish it.

It is possible for publishers to have a hybrid model, but only if they focus on subscriptions as primary and advertising as a secondary revenue source. For example, The Washington Post still displays ads for its paid subscribers (I'm a subscriber). It's worth noting that there is a fine line between charging readers to access your content and also annoying them with ads that might impact their experiences. Certainly, there is a risk of ad revenues negatively impacting subscriptions, the publisher's primary source of revenue.

But, as Thompson highlighted, the more niche publishers there are, the more likely they are to draw their revenue from subscriptions. There aren't many alternatives in niche topics and the limited total addressable audience (TAA) requires more loyal and engaged readers.

3.5. The importance of content cross-pollination

The number of media channels has expanded exponentially in the last few decades. Media producers can use multiple channels to build an audience. One of the most effective ways to improve your content reach is to reuse content across multiple channels. It doesn't mean that you just copy and paste content from one channel to another. Your content has to be adjusted to the new channel and in some cases recreated completely.

Let's say you have an idea for the article. First, you can write a quick tweet or a series of tweets getting some initial feedback on the topic. Then, you can expand this idea for a few paragraphs and share it with your newsletter subscribers. This will provide you with another round of potential feedback from your audience. Now, you might want to write a longer article on this topic and publish it on the blog. You can then record a podcast going over the ideas expressed in the article. And, finally, you can create a short video summarizing the content and post it on your YouTube channel. The same content could be shared and recreated in different formats and published on multiple channels.

In essence, content cross-pollination is a process of reusing and recreating content from one format to another and distributing it from one channel to another. Every time you see Tiktok videos on Twitter or an article summary in the newsletter or a Quora question linking to the article or a video it is content cross-pollination at work.

We will see more producers cross-pollinating their content across channels and in many formats. Creating a solid media product is difficult and it is worth maximizing the audiences it reaches. The best media producers recreate content in different formats and channels.

4. Publishers and Platforms

4.1. Editorial vs. Business — Diminishing power of the latter

A subscription model is poised to become the primary source of revenue for publications. But there is another important trend that impacts the publishing industry. Unlike in the pre-internet era, journalists and writers have tools to build their own audiences and to create their own content experiences and destinations. Is it possible for larger publications to disintegrate into smaller one or two-person teams? I believe it's unavoidable.

In the pre-internet era, publishers consisted of two distinct operations: business and editorial. Their relationship is often described by industry insiders as "the separation of church and state." Since I'm not an industry insider, it's hard for me to say which is which. But the idea is obvious: the business side focused on generating revenue, mostly through selling ads, while the editorial side was solely responsible for creating newsworthy stories. The business side had no voice in editorial matters to avoid conflicts of interest. After all, it seems as if editorial is the state in this analogy.

The separation of church and state in publishing was required to protect the integrity of journalists and shield readers from stories influenced by corporate money. Yet, publishers that focus on subscriptions as their monetization model do not need to cater to corporate advertisers. They can just focus on creating stories and serving their readers who pay them. It further empowers journalists and writers to start their own publications. The disintegration of large publishers and the rise of independent (niche) publication trends were recognized by a few platforms that came to service them.

4.2. Medium: a publisher or a platform?

While many thought digital content publishing couldn't get any easier, Ev Williams, who co-founded Blogger in 1999 and later Twitter, launched Medium platform in 2012. In the mission statement announcing the launch, Williams highlighted three main priorities for the platform:

- Create a beautiful space to post content so that creators can focus on content and not spend a tremendous amount of time coding and adjusting content presentation;

- Improve collaboration between writers and readers;

- Help writers find their audience (23).

Medium made it easy for anyone to publish and share content without the trouble of setting up and managing their own blog. But most importantly, it changed how we view content presentation and experience. Medium's simple and beautiful design made reading digital content fun and entertaining. On the other hand, writers could see how content would be presented during the editing process. What you see in editing mode is what you get when you publish your article.

For the first time, writers could embed different types of content such as images, videos, and links without any code. It's hard to overstate how much Medium has done to improve the content experience and pushed other publishing platforms to pay more attention to it. In the world of tangible goods, product packaging is as important to the overall product experience as the product itself. Everyone who ever opened an Apple product should agree.

In publishing, content is the product and its presentation (packaging) impacts the reading experience for the audience. With tangible products, customers only interact with packaging once. I use my Apple laptop daily but I have yet to go back to the beautiful packaging that it was sent in more than a year ago. In the world of content, its presentation and delivery continuously impact the reader's experience. Just change the font for your article to something that's harder to read and you will see how your experience will be affected immediately.

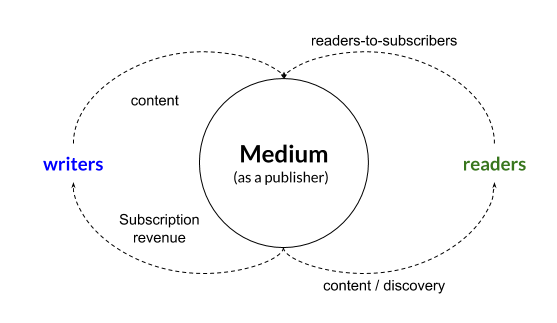

Medium showed that great presentation of content online can boost the performance of already great content.

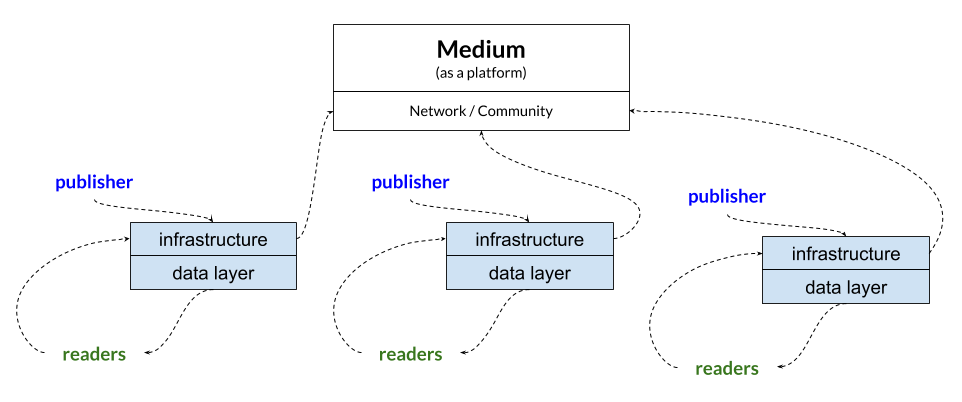

Nonetheless, it is still unclear whether Medium is a platform or a publisher. Over the years, Medium has claimed to be a platform, then a publisher, then a platform again. It launched advertising then shut it down. Medium recruited publishers, then closed its publisher's program, then opened it again. Medium can't be both a publisher and a platform. These business models are fundamentally different and require contrasting approaches, not just in how you build the product but in how you build your organizational structure. A publisher is in the business of creating content and growing readership. Medium saw an opportunity to build a new kind of publisher. Unlike traditional publications, Medium incentivizes an army of independent journalists and writers to produce a constant stream of good quality content. The advantage of Medium's approach is that it doesn't have to employ a large number of writers or any at all. It needs to grow its readership and figure out the best way to distribute revenue from subscriptions to the writers. This long-tail approach to content creation requires a solid content discovery algorithm to help readers get the stories on the topics they are most interested in. In this model, Medium stands in between writers and readers, distributing the revenue to the former and curating the content for the latter. It is similar to the Uber model where, instead of full-time taxi drivers, it employs independent drivers that can be part-time or full-time drivers. Anyone can drive for Uber just to earn extra cash. This increases the supply side of the marketplace.

A platform, on the other hand, provides tools for publishers to create and publish content, as well as engage and grow readerships and subscriptions. The responsibility for growing audiences lies in the hands of publishers, not the platform. The value of the platform comes from making it easy for publishers to create publications and engage readers. A platform provides infrastructure and data layers for publishers, allowing them to focus on content creation and building close relationships with their customers. A platform leaves it to publishers to create content and to grow their readership and subscriptions. As a publishing platform, Medium competes with WordPress, Ghost, Squarespace, and other CMS solutions. None of them were made with a focus on the content experience or the necessary tools to grow and engage the audience.

Medium could be successful using either model but it can't be both a publisher and platform at the same time. If you are a publisher, you have to focus on content discovery and readership growth. If you are a platform, you need to focus on infrastructure and readership engagement tools while accommodating the needs of publishers, or independent writers, to manage their publications.

As a platform, Medium could also provide unique content distribution services across publications that use their platform. They could highlight and promote articles across publishers and even aggregate them on specific topics.

However, Medium doesn't seem to be eager to build a true publishing platform, or what Ben Thompson calls a faceless publisher (24). Currently, Medium limits publishers in a few very important ways that prevent them from becoming a default platform.

First, Medium doesn't allow you to connect your own domain. For many content producers, writing is a way to build a voice, brand, and following among people who are interested in topics you write about.

Second, Medium mediates the relationship between writer and reader. Writers have almost no options to communicate with their readers directly. As someone who has managed to build a small audience on Medium writing about niche topics of marketing and product growth, I find the most frustrating aspect of Medium is that you can't email your followers or send them a direct message when a new article is published. Every time a new article is published, the writer has to rely on the Medium algorithm to put the story in front of the followers and enhance distribution among potential readers who haven't heard of you.

Third, every writer who takes content distribution seriously goes through a content distribution process that includes sharing your content in the newsletters or sharing it across social media channels where you have the following already (Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook). When readers end up on your Medium page they can follow you but there is no other way to capture your audience. There is no way to ask your readers for email. Hence all the traffic that the writer generates from distribution activities benefits Medium and its ecosystem but provides little help in accumulating and engaging audiences for writers. So every time you publish a new article you have to build readership for it practically from scratch. That's why we saw a few products on top of Medium that allow collecting emails from readers (for example, Upscribe).

It's not difficult to see why Medium's identity crisis — publisher vs. platform — became such a long struggle. Both strategies generated positive feedback from the market.

Medium-publisher provided readers with much broader and diverse content created by the army of independent writers and journalists. It's worth the subscription because you can't get content from such diverse topics from any other publication. On Medium, you can read about politics, sports, marketing, self-help, investing, parenting, economics, psychology, humor, music, and the list is practically endless. Even industry titans such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Atlantic with in-house editorials can't have such breadth of topics and diversity of opinions. You will have to spend hundreds of dollars subscribing to many niche publications to get the same variety of content and you will get on Medium for a fraction of the cost. This is the same reason why traditional taxi systems can't compete with the supply of Uber and Lyft.

Medium-platform gathered interest from multiple publications because it promised to solve their tech problems. Publishers are not great at luring technical talent or managing open-source platforms or building their own to stay on the top of the design, SEO, and performance best practices. Content must be good, but so must the design and experience. Pages must load fast anywhere in the world. The latest changes to search engine algorithms must be incorporated to maximize the search traffic. The content has to be shared easily on social media and not require downloading and meddling with the add-ons or plugins. Publishers must have an easy process of adding and managing new writers, aligned with current editorial approvals and workflows. And, most critically, publishers need their writers to focus on writing engaging stories and not on managing content management systems, messing with HTML and plugins, and resizing images. Yes, resizing images in WordPress is still a thing.

In addition, consider the technical aspect of shifting toward a subscription revenue model. Publishers must collect payments, manage subscriptions, gather usage analytics and personal preferences, and provide limited content free to generate audiences ready to subscribe.

But while Medium-platform tried to become a default platform for publishers of any size, it forgot one important caveat that we talked about earlier. Publishers, big or small, must own the relationship with their readers. It's not a nice-to-have, it's a must. Communicating with and receiving feedback from your audience is the key to building a successful publication.

Medium-publisher, like any publisher, must control the relationship with readers. Medium-platform must allow publishers to communicate directly with the readers. These goals are at odds with each other. Medium has to decide which path to choose to be successful. Trying to be both is the road to mediocre products at the least and failure of the company at most.

So when Medium doubled down on their goal to be a publisher it wasn't surprising to see publications leave. It's not only traditional publishers that left — The Ringer leaves for Vox, Backchannel moves to Wired, ThinkProgress leaves for WordPress — but also companies that built their blogs on Medium such as Signal v Noise by Basecamp, who left for WordPress. The momentum for Medium to build the next publishing platform for subscription generation was lost.

4.3. Vox Media: a platform play

Vox, on the other hand, recognized the market potential of providing an all-in-one platform for publishers. In the summer of 2018, Vox rolled out to the public Vox Chorus, an enterprise SaaS publishing platform. The platform, which is more than seven years old, Vox built to support its own publications. Their experience in publishing made them sensitive to the needs of the modern publisher.

Vox came to a similar conclusion we discussed earlier — writers and journalists hate their content management systems. Today, publishing is not only about content itself but about the experience that comes with it as well as content analytics and distribution capabilities. Vox Chorus even allows publishers to tap into their own ad network. The value of Chorus for publishers is clear — you worry about the content and we will provide the tools to help you publish, distribute, track, and generate revenue.

It is also clear that not only publishers can benefit from this publishing platform but enterprise brands as well. Every company is a media company. Hence, every company should have the tools necessary to run a media-like organization. This push makes traditional content management and blogging platforms inadequate for current needs.

But while Vox platform helps manage a publication, distribute content, and even generate content from ads, it still lacks the necessary tools for those publications that rely on subscription revenue. Furthermore, Vox Chorus is an enterprise system that is priced outside of the range of smaller and individual publishers.

Chorus is not the only platform that provides a publishing platform for large scale media organizations. It directly competes with Arc, a similar solution from The Washington Post. Both target the high end of the publishing market (25).

Chorus and Arc have the potential to capture a large customer base and solve the growing problems for publishers. Nevertheless, it's difficult to see how both of these products disrupt the publishing industry.

The most disruptive and innovative products are those that grow from the bottom-up. As Clayton Christensen outlined in his legendary book "The Innovator's Dilemma," the most disruptive products almost always offer lower performance and value in terms of attributes and features. These products are cheaper, smaller, simpler, and more convenient. Disruptive products open new markets and expand them starting from the bottom. So while Vox and The Washington Post have tremendous expertise in how publishing works in a large organization, they have little understanding of or interest in serving the growing new generation of publishers run by small and agile teams.

The 'mediafication' of the economy enables individuals and small teams to launch publications. Their needs and their budget cannot be addressed by Chorus or Arc solutions.

4.4. Substack: a platform for independent writers

Everyone is a media producer. And as more and more writers and journalists build their own audiences we see many products and platforms that help them reach a large audience.

If you are an independent writer, paying for an enterprise-level publishing platform is unattainable. You can't afford Chorus or Arc. On the other hand, traditional blogging and content publishing systems aren't providing you with the necessary tools to grow and engage your audiences.

This is what the team behind Substack recognized. They've noticed that many independent writers were trying to find a way to build an audience that would pay a small subscription fee to have access to their content. Writers don't want to deal with payments and call-to-actions to collect emails from subscribers as much as they don't want to deal with complicated content management systems.

Substack solves all of these problems by providing an easy platform to create a newsletter, manage subscription fees, and collect emails. And Substack allows its writers to own their relationship with readers and connect their domain. Thus, someone who starts their newsletter on Substack owns the relationship with readers.

It is clear that Substack wants to build a platform that enables media producers to build their audience and generate income. Aside from newsletters, they are experimenting with podcasts and there is a logical extension of their product into different media formats.

Substack is clearly an example of a platform that potentially can disrupt the publishing industry from the bottom up, meaning targeting independent writers and small teams rather than large publishers.

That's why Andreessen Horowitz led a Series A investment in Substack. Andrew Chen, Partner at a16z, built his own brand and career writing on the topics of growth hacking. He has experience in dealing with tools and platforms from the customer side. In the funding announcement, Chen underlined the trend that a new generation of media producers and creatives will be building their own audiences and generate income as a result. This is what he called the golden age of new media (26).

5. Selling content vs. selling using content

There are two strategies for media producers to make money. First, you can sell access to your content through subscription. In this case, the content itself is a product. Substack allows writers to start a subscription-based newsletter without having to deal with payments and the engineering side. Patreon is another product that helps creators generate recurring subscription revenue for creators. There will be an opportunity for other platforms to build a substantial business helping producers selling access to their videos. It is reasonable to expect some of them, like Substack, will focus on one specific channel such as a newsletter or podcast or videos, a vertical approach. Other products, like Patreon, will provide a horizontal platform for many channels and content types.

The second monetization strategy in the golden age of new media is generating revenue through selling products and services to the audience that you build through free content. In this case, your content generates an audience that later can buy your products or services. The key is to capture your audience by collecting their emails. You can also gate some of your premium content to help you grow the audience. David Perrell is a great example of this strategy. He writes a popular blog on broad topics, hosts a podcast, and sends two weekly emails. He generated a significant audience to whom he can now promote his Write of Passage workshop. Similarly, Tiago Forte creates high-quality content on a consistent basis. He uses free content to drive people to his premium subscription content as well as his online courses and workshops. For this monetization model, it's important to have tools to capture and manage your readership. Some of the content you can provide for free and some content could be partially gated or completely gated. This brings us to the content lifecycle.

The content lifecycle is an idea that content value and purpose changes over time. Let's say you are building a subscription-based publication. As you release your new article you can provide it only for paid subscribers. In six months the value of this content to your paid subscribers will decrease and you might want to make it available for anyone who wants to subscribe to your newsletter. You can generate more value and build an audience by allowing a broader audience to access this content. In a year, you might want to make this article available to everyone and even further expand the value from the content by allowing search engines to index it. This is a content lifecycle strategy to grow your audience even further.

Unfortunately, it's difficult for media producers, writers, and publishers to implement this content lifecycle strategy using current publishing tools. It was one of the reasons I started Publishnow, which is now defunct.

In spring 2018 I founded Publishnow, a publishing platform that makes it easy for anyone to start a publication, grow the audience, and generate revenue. In my experience as a writer and marketing consultant, I discovered that writers still have to spend significant time setting up their blogs. Even writers working on the corporate marketing team spend up to 30% of their time managing an outdated content management system. Our goal was to build a solution that allows writers to launch a publication without any IT help, code, plugins, or add-ons. Our focus was on building a product that writers could use to build audiences and simplify content production, distribution, and engagement. Pushlishnow connected to your Google docs and exported your article into Publishnow, including images, with one click. We made it easy to add calls-to-action across in the article and hide parts of the content, allowing you to have free access, email-gated, and, in the future, paid-only content.

For multiple reasons, we had to close Publishnow. However, I strongly believe that the idea of a new light publishing platform that focuses on optimizing a complete content production cycle is valid. And I expect a major platform to emerge in this space.

6. Conclusion: New Markets and Opportunities

Media makes everyone a content producer.

In the knowledge economy, regardless of your occupation, your career and income will correlate with the amount and quality of media you create. David Perell has popularized the term, “personal monopoly.” It is through producing media that you create the unique intersection of your knowledge, personality, and skills that nobody else can duplicate.

Sharing your expertise increases your visibility in the market and brings new opportunities. Additionally, there are now more opportunities to build an independent income stream, all of which include media and content creation. Many independent content producers — writers, podcasters, YouTubers, artists — will bypass the large middleman and build their own audiences and source of income.

Media rewires every organization.

Companies will have to build media production capabilities regardless of what they sell. Media production is the best marketing strategy. We will see organizations transition to adding a media layer to their organization. This is what I referred to as mediafication of the economy. This transition will require organizations to learn how to produce and distribute media products and invest in infrastructures that support agile media production practices.

Mediafication provides new opportunities for entrepreneurs and investors.

This transition will require a new set of tools and platforms. The technologies available only to a large cable network and national publications are becoming more affordable and accessible for every organization. New platforms and tools help you with video and podcast recording, editing, graphic design, distribution, and engagement.

To understand where new disruptive products will come from, we have to look closely into how content is created. Let's break down a media production process that's applicable to all media forms and content formats. For leaders and startup founders in any industry, it's an opportunity to decide how an organization must change to incorporate a media layer into its operations. In a practical sense, it means that every organization needs to have a continuous content/media production process.

The media production process includes five elements: 1) creation stage; 2) publishing stage; 3) distribution stage; 4) engagement stage; 5) analytics and measurement.

1. Creation Stage

In the beginning, goals are set, ideas are generated, scripts are written, and drafts are created. While tools can't guarantee a quality product, they can help you be more effective. There are already tools that help media producers create better content, such as Canva, which lets anyone create designs that can be used in blog posts or videos. Note-taking, knowledge management, text, video, and sound editing and processing tools are part of the creation stage.

2. Publishing Stage

Next, content gets published and content experience is designed. We should expect new platforms and tools that help content producers publish more easily and create content experiences that improve feedback. Imagine your publishing platform allowing you to add interactive polls to your article or even dynamic visualizations. Traditional CMSs are outdated and do not serve the needs of today's creators.

3. Distribution Stage

Now, as the content is created and published, the team needs to follow its distribution plans. Distribution is one of the most overlooked functions when it comes to media and content. Traditional media organizations pay a lot of attention to distribution and ratings, but in companies that don't have a media company mentality, they are often overlooked. Simply publishing your video on a YouTube channel or posting an article on your blog is not enough — that doesn't constitute a distribution strategy. New products in this category can help you find where this content can be reused, such as related Quora questions or LinkedIn groups. Furthermore, every new article can automatically connect with your paid acquisition campaign, which in time will help distribution.

4. Engagement Stage

It’s not enough to attract the audience to the content. You have to engage them. Every visit, every eyeball is an opportunity to engage. If you are releasing an article, does it help you grow your newsletter list? Do readers share it? Do people leave comments? Do they engage with your content on social media? New publishing platforms will allow producers to collect feedback and communicate with the audience more effectively.

5. Analytics and Data

Analytics and data should be collected at every stage of the media cycle. This data layer will help you drive your decisions on what to create, how to publish it, what to improve, and how to increase revenue either by driving customers to premium content or by cross-selling your products and services.

6.1. Summary: The Future of Media and Publishing

- We have transitioned from a few large offline publications to countless smaller online publications that cover niche topics. The number of niche publications will grow exponentially.

- Publishers, especially niche ones, will rely more on subscriptions than ad revenue. The niche model is predictable and scalable and the subscription model enables publishers to build direct relationships with their readers.

- Every person is a media entity. Today, everyone is a content publisher, and more and more people are producing content to make money directly or use it to drive customers to other products and services.

- Regardless of your career interests, building an audience tremendously enhances your chances of rising to the top of the industry. In the knowledge economy, your career and income will correlate with the amount and quality of media you create.

- A successful media operation requires both content production and a distribution strategy. The cost of content production and distribution will continue to decrease and will be forever approaching $0 (see Zeno paradox).

- Content consumers will have a greater impact on producers. Technology will continue to improve the speed and quality of the feedback loop between producers and consumers.

- Media producers reuse content across multiple channels, increasing its reach.

- We will see many more platforms and products that help publish beautiful content, engage readers, analyze data, capture audiences, manage subscriptions, and own the relationship with the audience.

Thank you reading and sharing.

And a big thank you to my editor Steve Schaefer.